Fascinating! Reposted from the Times via Energy in Demand:

Scientists have developed a prototype window that can harvest heat in the winter and reflect it in the summer

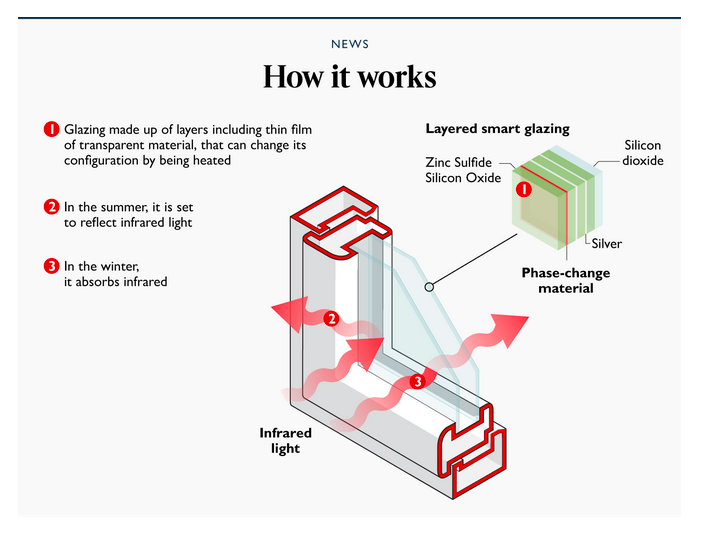

A prototype window with switchable absorption properties, so that it can be set to harvest heat in the winter and reflect it in the summer, has recently been developed. The window relies on a film just 12 nanometres thick, containing a material that changes its state when heated up to high temperatures, using a transparent heater. A transparent heater causes a structural realignment of the atoms within, shifting them between a crystalline and non-crystalline state and so altering their properties. The heater only has to be used for a fraction of a second to effect the change. Tom Whipple discusses latest developments in an article on The Times website.

Turn on the windows to keep warm

When winter comes, it is time to switch on the heating — and, perhaps, switch on the windows too?

Scientists have developed a prototype window with switchable absorption properties, so that it can be set to harvest heat in the winter and reflect it in the summer.

Crucially, in a paper in the journal ACS Photonics, they show it does so without becoming visibly darker to those in the house, as the material used is highly selective in the wavelengths of light it absorbs or reflects.

The window relies on a film just 12 nanometres thick, containing a material that changes its state when heated up to high temperatures, using a transparent heater.

A transparent heater causes a structural realignment of the atoms within, shifting them between a crystalline and non-crystalline state and so altering their properties. The heater only has to be used for a fraction of a second to effect the change.

In one state, the film reflects infrared light, keeping the room beyond cooler. In another, it absorbs the light, reradiating it into the room. In this way, the scientists believe they can improve the energy efficiency of standard double glazing by a fifth to a third.

“Importantly, visible light is transmitted almost identically in both states, so you wouldn’t notice the change in the window,” said Nathan Youngblood, from the University of Pittsburgh.

Currently, the researchers have only tried out the film on a very small panel of glass. In order to commercialise the technology, Youngblood and his colleagues need to test the technique on a window-sized area, which will also involve distributing the heating.

Ultimately, said Youngblood, they want to connect it to smart sensors, which adjust according to temperature and sunlight.

“There would be benefits to switching back and forth. Even in the winter, depending on the outdoor and internal temperature and the lighting from the sun, you may want to switch it,” he said.

Harish Bhaskaran, from Oxford University, collaborated on the work. He said there were obviously challenges ahead, but he was hopeful.

“Although significant future research is necessary before this technology can be commercialised, the results show that the concept is very promising and with further research can achieve very good efficiencies.”